The following is part of a series of posts written by 2016 MPSA award recipients highlighting outstanding research presented at previous MPSA annual conferences.

What power do religious authorities exert over people? While the traditional role of churches and clergy as nurturers of social capital has declined with the secularization of the West, the importance of religious actors in large-scale social and political mobilization in the non-Western world has been steadily increasing for many years. Both government policy campaigns and anti-government protests find themselves sinking or swimming depending on their ability to “connect with the society… [and] maximize the use of traditional and religious leaders.” Muslim clerics serve as the backbone of social service and militant fundraising for organizations such as Hezbollah and the Mahdi Army in Iraq, and conversely, the ‘de-radicalization’ of terrorists. Clearly, religious authorities wield unusual influence over people; but what this influence is and how it works is a mystery.

One possible explanation for the effectiveness of religious authorities as mobilizers may be that especially charismatic and persuasive individuals are overrepresented in this profession. Ruhollah Khomeini may have personality traits that would have made him a powerful a leader, whether as Grand Ayatollah or as a secular authority figure. However, personal characteristics aside, being perceived as a religious authority may imbue an individual with unique psychological powers. The most obvious one may be that religious authorities are implicitly associated with God, and hence automatically remind people of higher ideals, being perfectly observed by God’s omnipresence, and after-life rewards and punishments. This is far more powerful than an alternative channel, which is that religious authorities influence people by virtue of their position as community leaders and enforcers of norms.

Investigating these competing hypotheses is difficult with existing data. Personal characteristics that distinguish religious authorities and civilian authorities are difficult to categorize, let alone measure. In situations like this, where counterfactuals are often impossible to establish with real-world data, experimentation plays a central role. A few studies manipulate the identity of the deliverer of a message to be from a religious authority in writing, through video, or in the form of a picture. However, “the most subtle dynamics ..[on].. how relative status is signaled and established depend on the resources made available by face to face interaction and a shared physical setting.”

We present the first experiment we know of to do just this. In our experiment, a Muslim cleric in Kabul, Afghanistan appears in person to solicit contributions for a public good (a hospital) from low income day laborers under two experimental conditions: while dressed as a civilian (Civilian) and while dressed as a cleric (Cleric). By having an actual cleric interact face-to-face with the subjects, we isolate the additional impact of his positional authority after preserving the multidimensional characteristics (speech, gesture, etc.) of an individual that would self-select into this high-status position. Indeed, the cleric’s distinction is apparent even in his civilian clothing: 80% of subjects who guessed his profession stated professions of secular authority.

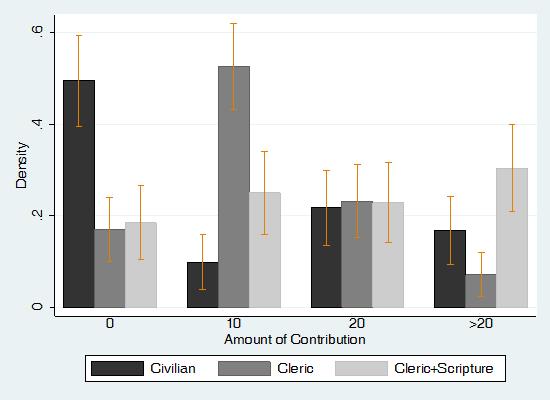

We find that people are far less likely to contribute nothing (0 AFN) to the hospital when the solicitor is dressed in his clerical garments (17%) compared to when he is dressed as a civilian (50%) (see Figure 1). However, average contributions are equal across the conditions because while more people give when asked by the cleric, (a) they give minimally (10 AFN) and (b) the decrease in conditional amount is especially pronounced among those with formal education. While civilians do not wield verbatim quotations of scripture as a motivating and legitimating tool, clerics do. We therefore add a third treatment, the Cleric+Scripture treatment, which proceeds identically to the Cleric treatment except for an addition of a short reading from the Qur’an at the end of the solicitation script reminding subjects that “Allah loves good-doers”. The use of religious text is among several known ways to explicitly prime religion in the experimental and behavioral literature, and consistent with this literature we find that conditional amount increases while the probability of giving remains high. As a result, average contributions in Cleric+Scripture are twice of that in the Civilian and Cleric conditions.

How should we explain this behavior? First and foremost, our evidence suggests that religious priming comes from the Qur’an, not the cleric. The increase in the intensive and extensive margins of giving that is observed in previous experiments with religious priming only occurs in our experiment with the addition of the scripture. Second, the increase in the propensity to contribute, coupled with the decrease in conditional contribution to the smallest possible denomination of 10 AFN, suggest that the day workers in our experiment were complying with the Islamic norm of sadaqah (charitable giving) in a way consistent with legalism, that is, an adherence to the letter but not the spirit of the norm. In other words, religious positional authority appears to place the cleric as a legitimate leader of the Muslim community, but without the rhetorical tools of scripture, not one that is implicitly associated with an omnipresent God (otherwise, this would suggest that while God can observe whether you give, he apparently cannot count). Third, those who are formally educated appears to be less receptive to religious positional authority. Overall, our experiment illustrates the limits to the positional power of religious authorities and shows just how important holy scriptures can be as justification for the cleric’s exhortation or as a direct reminder that God is watching and rewarding the behavior that the cleric is encouraging.

About the Authors: Blog post submitted by Luke N. Condra, Mohammad Isaqzadeh, and Sera Linardi. Their research, “Clerics and Scriptures: Experimentally Disentangling the Influence of Religious Authority in Afghanistan” was named as a co-winner of the Kellogg/Notre Dame Award for best paper in comparative politics at the 2016 MPSA Conference.

About the Authors: Blog post submitted by Luke N. Condra, Mohammad Isaqzadeh, and Sera Linardi. Their research, “Clerics and Scriptures: Experimentally Disentangling the Influence of Religious Authority in Afghanistan” was named as a co-winner of the Kellogg/Notre Dame Award for best paper in comparative politics at the 2016 MPSA Conference.