By Michelle M. Hicks, Willamette University

Who are the “others” inside the U.S. carceral system? According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the “other” is any race, which cannot be classified as White, Black, or Hispanic.[1] The “other” category is an amalgam of racial identities that do not fit in the above categories including American Indian, Asian, Asian-American, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian, Alaskan Native, or anyone who identifies as multiracial. “Others” make up 9% of the state and federal prison population but are largely ignored within modern carceral discourse due to their small numbers, diversity, and inability to fit within the racial binary. [2] Traditionally, this category is not disaggregated, which is problematic because it glosses over the rich diversity present within these cultures. This creates a dearth of knowledge that is reflected through the scholarly focus on “black and white” issues and the continuation of the “othering” of Asian Pacific Islanders (APIs), one of the largest incarcerated groups within the “other” label, in academic works.[3] It not only omits important cultural phenomena but also makes it unclear whom scientists are actually referring to. Additionally, it does not account for the social, economic, and cultural differences in the API incarcerated population, thus homogenizing APIs with all of the “others” incarcerated.

The presence of APIs in the carceral state has skyrocketed in the past two decades to more than 10,000 incarcerated APIs.[4] This paper focuses on their specific experiences inside the Oregon state prison system and how their API identity shapes their experience being incarcerated. Even though APIs are one of the fastest growing groups of incarcerated peoples nationwide, there is an absence of research and resources allocated to understanding this phenomenon and the APIs who are trapped inside the carceral state. Their absence is especially visible in Oregon due to its small population of API identifying people.[5] When an individual becomes incarcerated, the repercussions reverberate through the entire API community. The label of API contains a multitude of cultures, immigration/residency statuses, religions, languages, and histories that contribute to the rich identity of these incarcerated persons. As a result, it is difficult for political scientists to conduct research or collect data with regards to the individual groups that constitutes the API label. In turn, this leads to further misconceptions about the experiences of incarcerated peoples, which has created the current neglect and the further marginalization of APIs in the academic sphere.

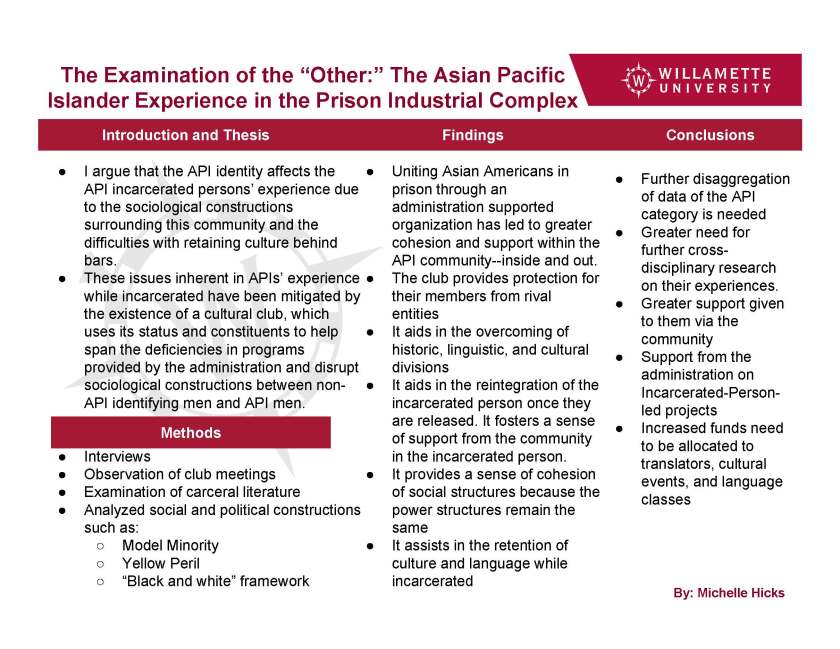

Additionally, there are many societal misconceptions that lead to further marginalization of APIs. There are few resources allocated to understanding and addressing API incarcerated peoples and how best to accommodate communal needs such as translation services, cultural identity, and loss of homeland. There have been numerous social constructions limiting the interpretation of this community inside the carceral state. To dispel some of the notions contrived from the Yellow Peril threat and Model Minority myth with regards to the API community, I conducted a series of interviews with members of an API club in Oregon. In my poster presentation, I argued that the API identity affects the API incarcerated persons’ experience due to the sociological constructions surrounding this community and the difficulties with retaining culture behind bars. These issues inherent in APIs’ experience while incarcerated have been mitigated by the existence of a cultural club, which uses its status and constituents to help span the deficiencies in programs provided by the administration and disrupt sociological constructions between non-API identifying men and API men.

The work that the club has done can be supported on a broader scale by supporting (either fiscally or with your time) any of the organizations listed below. Furthermore when conducting one’s own research, it is vital to disaggregate API category to gain a clearer picture of what the API community is like, who is affected, and how to better care for their needs. I am incredibly grateful to the MPSA for providing me with this award and platform to share my work.

About the Author: Michelle M. Hicks is a student at Williamette University in Salem, Oregon. Hicks received the Best Undergraduate Paper Presented in a Poster Format for her research titled “’The Examination of the “Other:’ An Insight Into The Asian Pacific Islander Experience in the Prison Industrial Complex” presented at the 2018 MPSA conference.

About the Author: Michelle M. Hicks is a student at Williamette University in Salem, Oregon. Hicks received the Best Undergraduate Paper Presented in a Poster Format for her research titled “’The Examination of the “Other:’ An Insight Into The Asian Pacific Islander Experience in the Prison Industrial Complex” presented at the 2018 MPSA conference.

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice

- Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund

- American Civil Liberties Union

- Asian Counseling and Referral Service (ACRS)

- Amnesty International

- Asian Law Caucus

- Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance AFL-CIO

- Asian Pacific American Legal Center

- Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO)

- Asian Incarcerated person Support Committee (APSC)

- Empowering Pacific Islander Communities (EPIC)

- Formerly Incarcerated Group Healing Together (FIGHT)

- Healing Garden Oregon State Penitentiary

- Innocence Project

- Just Detention International

- Legal Services for Incarcerated persons With Children

- Marshall Project

- Prison Policy Initiative

- Sentencing Project

- Until We Are All Free

- White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders

Footnotes

1. United States. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prisoners in 2015….

2. Ibid.

3. “Asian Americans and Pacific….”

This pamphlet statistically analyses the “other” population nationwide, with a focus on California.

4. Brian D. Johnson, and Sara Betsinger. “Punishing the ‘Model Minority’ Asian-American Criminal Sentencing Outcomes in Federal District Courts.” American Society of Criminology 47, no. 4 (2009): 1045-1089

5. Ibid.